Trophy hunting ‘benefits’ in Botswana’s NG13 stolen by hunting operator and local elites

Financial audit reveals rampant corruption in one of Botswana’s key trophy hunting areas.

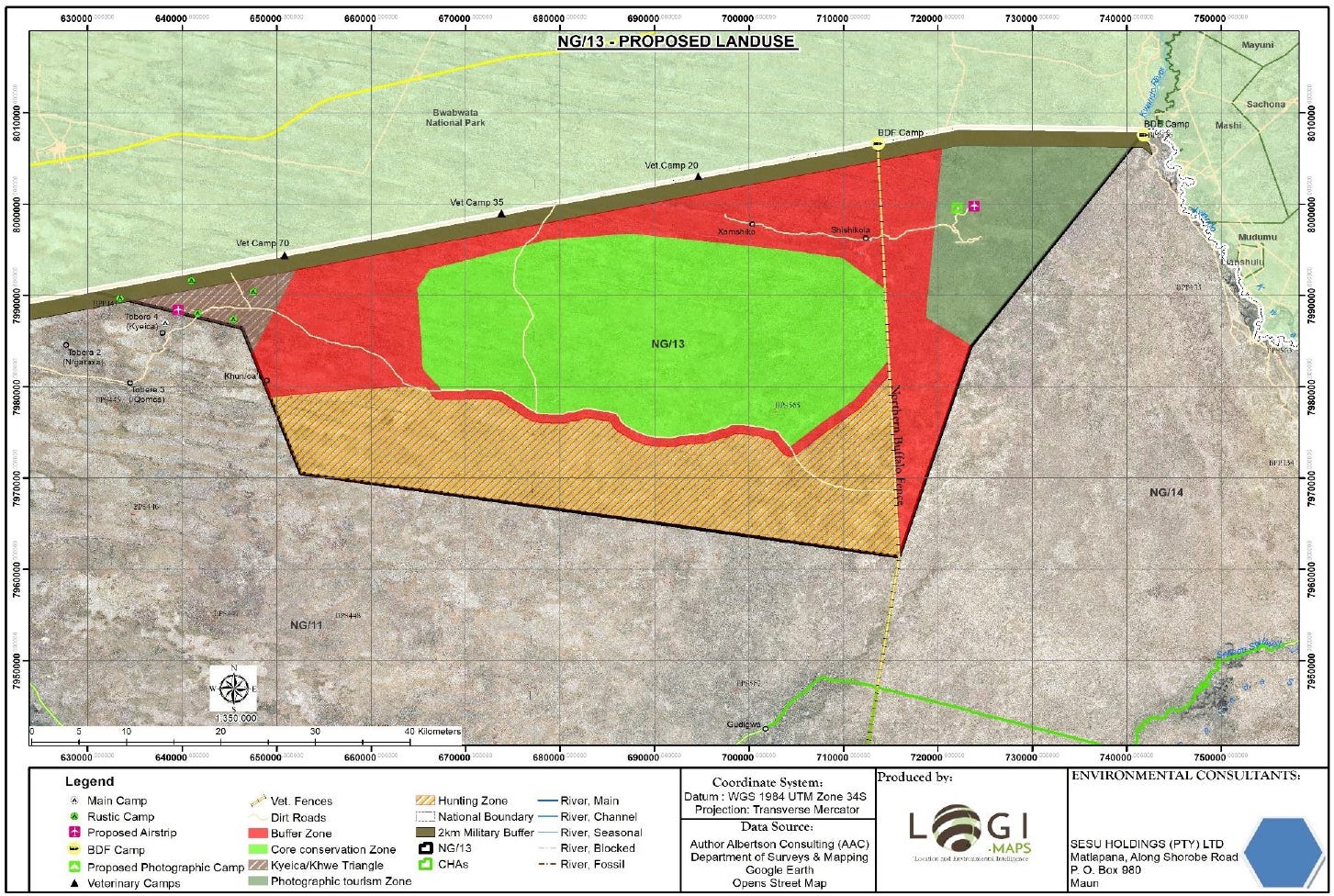

Botswana’s NG13 is a mixed-use area on the border of the Namibian panhandle near the Okavango Delta. A quarter of NG13’s land is for trophy hunting. The region features highly-prized elephants desired by the international trophy hunting industry.

Trophy hunting in NG13 is supposed to benefit the 627 households in the Kaputura, Tobere, and Kyeica communities. Income from trophy hunting quota sales should flow through the Tcheku Community Trust and into the three communities.

The Trust comprises nine elected board members (three from each community), a general manager, an accounts officer, and nine escort guides. The Technical Advisory Committee oversees the initiation and implementation of Community Based Natural Resources Management projects for the Trust.

Old Man’s Pan Proprietary Limited, run by businessman Derek Brink and professional hunter Leon Kachelhoffer, was granted a monopoly over NG13’s trophy hunting access (Brink passed away in early 2023. Derek Brink Jr is now involved in the business). It is the sole trophy hunting operator responsible for funding the Trust.

Sustainable use activists point to Botswana’s NG13 as a prime example of how trophy hunting can generate income and jobs for impoverished communities. But all is not as it appears.

A 2022 Sunday Standard investigation found that Brink and Kachelhoffer forced the Trust to accept an elephant hunting quota at less than a third of the market rate. Community members became increasingly frustrated with the Trust and the exploitative relationship with Old Man’s Pan. They alleged misuse of funds by the Trust and requested a financial audit.

I obtained a leaked copy of the Tcheku Community Trust internal audit report. The audit revealed rampant corruption. Most funds and jobs went to the hunting operator and Trust staff members instead of the communities.

Old Man’s Pan obtained sweetheart deals from the Trust and effectively stole tens of thousands of dollars from the communities by failing to pay what it owed.

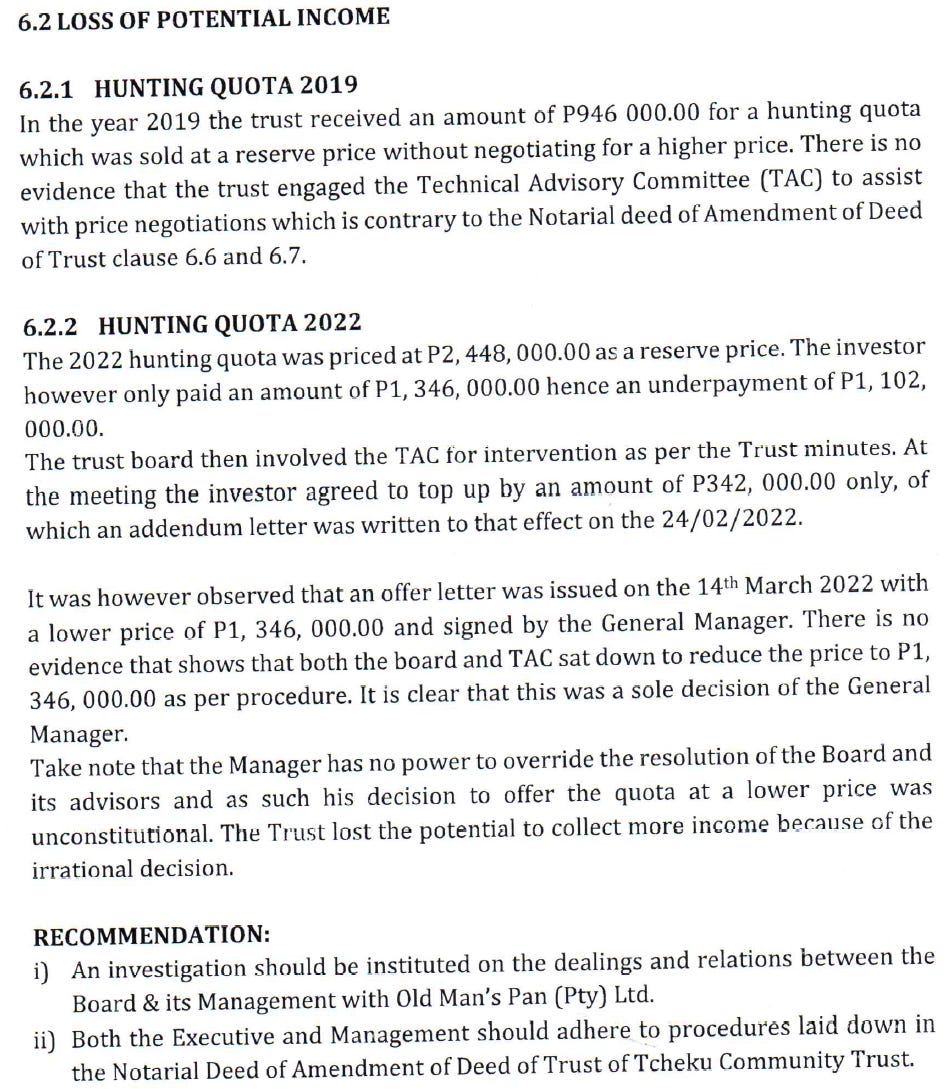

The Trust received $69,400 (P946,000) for a hunting quota in 2019 but did not negotiate a higher price. There was no evidence that the Trust engaged the TAC to help negotiate a higher price despite being a requirement in the Notarial deed of Amendment deed of the Trust’s clauses.

The 2022 hunting quota price was $179,500 (P2,448,000), but Old Man’s Pan only paid the Trust $98,700 (P1,346,000). The Trust board involved the TAC causing Old Man’s Pan to agree to pay an additional $25,000 (P342,000) in February 2022.

However, the Trust general manager signed an offer letter for $98,700 (P1,346,000) in March 2022. There was no evidence that the board and TAC agreed to reduce the hunting quota price.

The general manager had no power to override the board and TAC. Their action was unconstitutional. The audit report described the reduced offer as an “irrational decision.” It recommended that “[a]n investigation should be instituted on the dealings and relations between the Board & its Management with Old Man’s Pan (Pty) Ltd.”

Old Man’s Pan effectively stole $80,800 (P1,102,000) from Botswana’s NG13 communities in 2022. The hunting operator pocketed 45% of the trophy hunting funds earmarked for the communities.

The Trust’s eleven staff members’ salaries amounted to $32,000 (P435,000), or 32% of the $98,700 (P1,346,000) that the Trust received from the 2022 hunting quota. The audit report stated that “the remunerations are too high taking into account the fact that the Trust’s income is erratic.”

The accounts officer’s salary increased from $403 (P5,500) to $476 (P6,500) in September 2022 without any justification. Evidence suggested it was a management decision without board input.

Old Man’s Pan and eleven unelected Trust staff members received 63% of the $179,500 (P2,448,000) originally intended to benefit the NG13 communities in 2022 (NOTE: the original benefit amount is only a fraction of the total value of what international trophy hunters paid Old Man’s Pan to access NG13). A measly $66,800 (P911,000) for the communities’ 627 households, or $106 (P1,453) per household, was leftover.

The leftover benefits overestimate what the communities likely received since the audit also found evidence of unauthorized payments and embezzlement elsewhere in the Trust.

The Trust general manager initiated financial decisions without board approval. Management gave staff members advances in 2022 without proper guidelines causing insufficient funds to pay later months’ salaries.

The Trust loaned $5,200 (P71,000) without board approval to the Ngamiland Council of Non-Governmental Organizations in 2021. NCONGO repaid the loan, but a 2022 unauthorized loan of $5,100 (P70,000) to NCONGO remained unpaid at the time of the audit in March 2023.

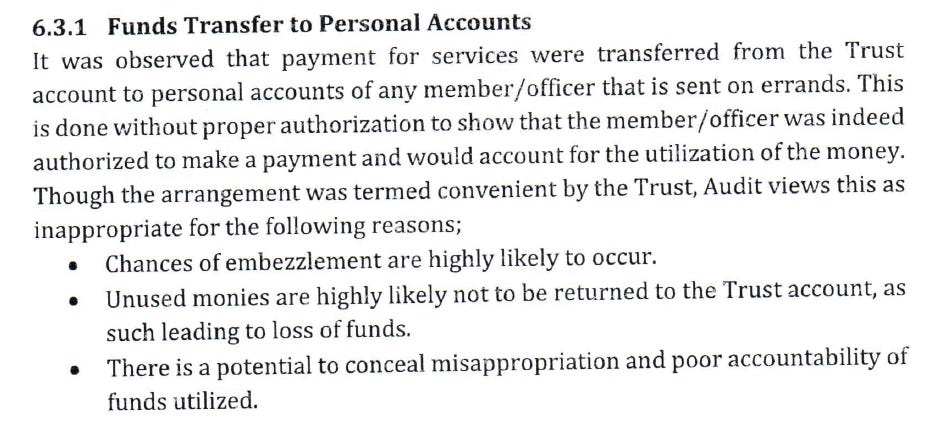

The Trust transferred unauthorized payments to members' personal accounts that went on errands. The audit report noted that “[c]hances for embezzlement are highly likely to occur” and that there “is a potential to conceal misappropriation and poor accountability of funds utilized.”

A former board chairperson and general manager bought a used Toyota Land Cruiser for $10,300 (P140,000) in 2021 without board consent and against the advice of the TAC. The used vehicle required repairs which ended up not working.

The general manager engaged Old Man’s Pan to assist with the repairs when the Trust ran out of funds. The board did not consent to the repairs, and the repair's costs were undisclosed.

The Trust also bought a Toyota Prado with the assistance of Old Man’s Pan for $8,800 (P120,000). The vehicle was involved in an accident when driven by a former Trust chairperson. The former chairperson drove without a license, and the Trust did not report the accident to the police.

The former chairperson faced no action. But the vehicle was repaired by the Trust at an unknown cost.

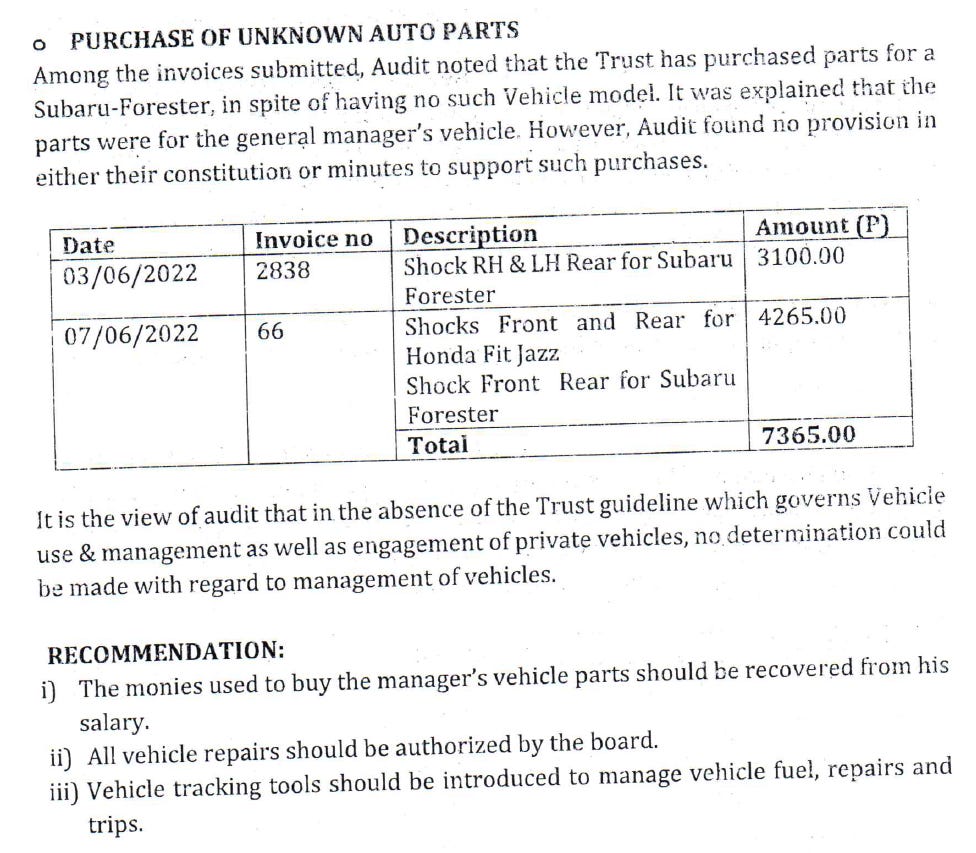

The Trust spent $540 (P7,365) on parts for an unlisted Subaru Forester in 2022. The audit determined that the vehicle parts were for the general manager. There was no evidence to suggest that the purchases were constitutional or authorized.

Trust staff members also stole jobs from the community. The Trust needed escort guides after the sale of the first hunting quota. Six members of the Trust board left their positions and became escort guides.

The Trust did not advertise the jobs to the communities, and community members never had an opportunity to apply. The audit report stated that “the board members used their position to their advantage and as such disadvantaging other Community members in the process.”

The audit’s report included poor budget implementation and poor record keeping. It concluded that “[t]he Trust’s internal control system is weak, as such it could lead to fraudulent practices and losses. Poor record keeping of the Income and Expenditure may result in violation of the requirements of financial regulations.”

The narrative that NG13 communities receive meaningful benefits from trophy hunting in the form of funds and jobs is simplistic and misleading. It’s an exploitative deal for the Kaputura, Tobere, and Kyeica communities.

Community members are afraid to speak out but want their stories heard. Others must spread the truth about who benefits from trophy hunting in Botswana’s NG13.

Final note: Sustainable activists will undoubtedly ask for an alternative way to fund the communities without trophy hunting in Botswana’s NG13. They’ll say that phototourism is no better blah, blah, blah. They, and most conservationists, will conveniently ignore where most of the money goes in the NG13 trophy hunting scheme: the Brinks.

The Brinks are one of Botswana’s wealthiest families (one estimate had Derek Brink’s net worth over $700,000,000). The alternative to trophy hunting is simple. Tax the Brinks’ wealth. Redistribute their wealth to the Kaputura, Tobere, and Kyeica communities.